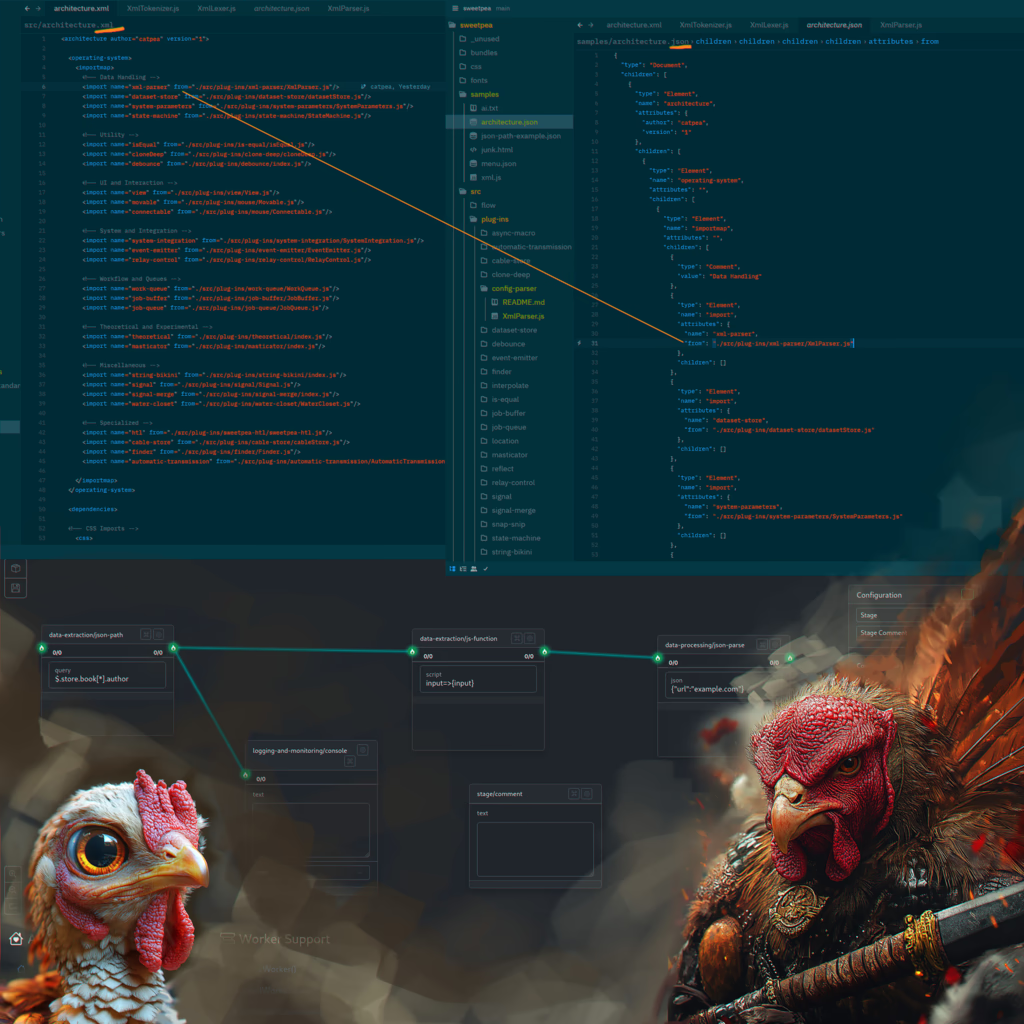

The Tokenizer and Lexer Story; Or, A Closer Look At XML Shenanigans

Just a few weeks ago I mentioned it is not possible to parse XML, with regular expressions, but yesterday I had a fun time doing just that.

This is because well made Configuration Files do not nest the same elements, it is OK to have siblings with the same name, but nesting is different.

Because the opening tag will not be able to recognize its closing tag, when it has another instance of it self within it self.

So when you say open box, and then again open a new box inside the open box, you now have two box closing tags, and they look the same to naive parsers like mine.

If an XML file is made with this in mind, and never nests the same thing, within it self, then it will work fine.

My XML parser can be further reduced to just one line of code here, but nesting elements or tags with the same name will not work.

The miniature program just grabs the first closing that it sees, and when things are nested like a Russian doll, that will not be the right one.

I woke up this morning, and without thinking about my code, and not wanting to test it…

I just said to myself, regular expressions, the technology I relied on, cannot do that.

And I know this from attempts at parsing XML, back when it was cool, and programmers randomly mention this.

But they may not know, the problem is only with nesting the same tags, if it is a configuration file, it will work.

But if it is a document with formatting boxes, and they can be nested, nope, it will be the wrong closing tag.

To popery parse an XML file, you need two unique technologies, a tokenizer and a lexer.

The tokenizer crawls the XML document from the first character, to the last, ignoring new lines it just sees a long line.

Tokenizer, extracts tokens, and you have to register patters or rules that it should recognize.

Xml continues being extremly self similar, so there are only six patterns, that is a small number.

Because we are eating every letter of the file, we have to process spaces and new lines, throwing them away.

And then there is the convenient self closing tag, instead of creating a closing tag you use a forward slash in the opening tag.

Then there is the open tag, and the close tag.

And text, or letters that are not enclosed in any special brackets.

And finally a code comment, which are always ignored, like spaces.

So you feed in the xml file as a long string of characters, and you apply each of these rules or patterns.

Until one matches, and consumes some of the characters,

For example, an opening tag called button, would eat 8 lettters, two brackets and the word button.

The brackets, or the surrounding less than, and greater than signs, are there to tell the tokenizes, that this is an element and not some text.

And slowly few characters at a time, we convert the long string, into tokens, objects that have a name, type, position in raw text.

And if the process arrives at something, that was not specifed by a rule, then we crash on purpose, because we discovered malformed XML.

That is a syntax error, nothing that the computer can recover from, you need to go in there and fix your typos, and ensure all your tags are closed.

The result is a flat list of tokens, no nesting, just a list of what we matched, in the original sting of text, of the xml document.

And at this point all the hard work is done, a simple tokenizer has an outer loop, just jumps past what was claimed by a token.

And that iner loop, where the new beginning that we just jumped to, is evaluated by the rules.

The resulting list of token is then returned to the main program, and sent to the Lexer, for Lexical analisis.

The lexer converts the tidy list of tokens into elements, actual objects, that live in a nested tree.

Whenever an open tag is found, it is added to the tree, to build the resulting document up.

Then added to a stack, and set as the new parent for elements that follow.

We go as deep as possible though all the opening tags, building a tree, until a deepest tag becomes a parent.

And because it is the deepest tag, it gets closed right away.

And now its outer tag becomes the parent again, as that nested tag is now correctly placed in the tree.

Here we may open a new tag, if there was stuff below it, for example an image beneath a title.

But slowly, we start making our way back, out the deepest parts of the tree, emptying our stack of parents.

And finally, having the lexer, return the now fully inflated tree.

That a moment ago, was just our tokens, informing us of opening and closing instructions.

Here our tree, called the abstract syntax tree, is returned to whatever requested the parsing of our XML document.